What is Interstitial Journaling?

It’s a stunningly simple technique that is a gateway to a host of benefits. At its heart, it’s simply a way of logging your day, but when done consistently and with intent, you can discover more about yourself and improve your work.

I first heard about this technique from an article by Tony Stubblebine. In his article, he described how it was “something you can make a habit out of. Finished a project? Habitually flip over to your journal, write the time down, reflect on what you just did, then reflect on what you’re about to do.”

It almost sounds too simple to work, doesn’t it? Simple, trusted systems which augment and compensate for our brains limitations are desirable because straightforward systems are easier to stick with and build habits upon.

By practising Interstitial Journaling, you’ll see how you spend your time, both productively and unproductively, and it helps shine a light on the work you do and how long it actually takes.

Through this simple habit, as Tracy Winchell puts it, you will begin to see your time and attention leaks. And when you can see these things in front of you, it’s far easier to formulate strategies to tackle and improve them.

As humans, we are notoriously bad at estimating how long something takes. Unfortunately, we are also pretty poor at planning too. Interstitial Journaling (IJ) can help with both of those.

Fixing your time leaks

The first step to figuring out where your time goes is really understanding how long things actually take. This is a perennial problem, but there’s an elementary solution. Keep a time log. This isn’t a new solution; Peter Drucker, in his book, The Effective Executive, was advocating this as a necessary first step toward becoming effective way back in the ’60s. So you would think this was a long-solved problem, but it’s probably even more difficult today. We have more demands and more distractions than ever before, and that’s why IJ can be a superpower when you use a tool like Roam Research as your note-taking application.

It encourages short, sharp atomic pieces, and that’s all we need. Log the time now, and write what you’re about to do. Once you’re done, note the time again. Now you know precisely how long that took you. (With Roam, extensions can make this time-logging task faster and can even calculate how much time elapsed automatically.)

If feedback doesn’t follow soon after an experience, then we won’t learn from it. – Sönke Ahrens, How to take Smart Notes

Building this consistent habit of coming back to your journal between each discrete task is the key.

If we leave this too long, our cognitive biases kick in and distort our memory of the events. We easily fool ourselves about how long something took, and then we can’t learn effectively from our past behaviour.

This technique also gives you opportunities to break your work into smaller chunks. Doing this means you will more accurately identify its components, and over time you can learn how long each part will take on aggregate.

When we can more accurately predict how long something will take us, then we set more realistic expectations for the day. It’s far more satisfying to have completed all the TODOs you planned than finishing the day with only half or fewer completed.

Most IJ articles will just tell you to log a time and then write your entry. That’s perfectly fine; however, I highly recommend using a time range. So when you start, write the starting timestamp and then a dash, e.g. 10:41 - . It will more easily encourage you to come back and complete it. It’s leaving a little open loop, a breadcrumb, to bring you back.

There are some other advantages it affords you. You will forget to IJ (often at first). If you consistently use time ranges, it will make it easier to see the gaps when you failed to return to your journal. If you cannot be sure what you spent your time on, leave it, and start the next section anew. When you review your entries for the day, it can reveal patterns in managing your attention. When you begin the next section, try to write out why you forgot to come back. What happened? Then you can work on why, and make changes to try to improve in the future. When you make the invisible visible, you have more chances to change for the better.

Tight feedback loops

In Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman & Amos Tversky distinguish between our fast thinking, making decisions from instinct or distorted by cognitive bias, and thinking more slowly by cogitating and using reason.

Temporal landmarks give us a natural chance to think more slowly. For example, New Year’s Day is typically when we think deliberately about what we want to achieve in the coming year. On a shorter timeframe, perhaps when we start our workday, we write out what we hope to get done today. At the end of your day or in the evening, if you’re diligent, you might review how the day went. But even that timeframe is far too long. If I asked you to list out everything you did, you would miss several important things, and almost certainly, you would not be accurate in the time you actually spent on each of those things.

The rule says that when we remember we assign the greatest weight to its most intense moment (the peak) and how it culminates (the end). We downplay how long an episode lasts – Kahneman calls it “duration neglect” – and magnify what happens at the end. –Daniel Pink, When.

If you wait until the end of the day, or worse, the following morning, then your memory will already have skipped or forgotten the more mundane things. It’s often these moments that are the key to improving our days, though. Of course, we remember the exciting thing or the terrible thing. And we remember what we did last; it’s the freshest memory. What we don’t remember are all the attention leaks.

How many times do you think, ” it can’t possibly have taken that long to do this task “, or ” where’s my time gone?”. More than likely, it was because you got distracted by something or someone. Then, because it wasn’t the most exciting or last thing you did, your memory happily drops it because it’s no longer relevant. Except these gaps add up, and they’re hidden from us in plain sight.

I’m sure you’ll know from bitter experience how you can easily lose a lot of time to distractions like Twitter or Facebook. Your attention wavers, and you will just have a “2-minute” break and take a brief look at Twitter. Twenty minutes of scrolling and clicking later, you look up - probably because someone or something else distracted you, and not because you realised you were actually supposed to be working on something.

Since IJ is a lightweight technique done consistently, it can give you a very tight feedback loop. By shortening the feedback loop between your work and reflecting on it, you will notice with far more accuracy the quirks of behaviour that are holding you back or which power you forward. IJ give us this chance multiple times per day.

Fixing your attention leaks

Improving estimates is the first domino. It’s an easy thing to focus on, and there are a ton of benefits. But that’s just the start. When you are consistently journaling in this way, the next step is to take more control of your day and use the frequent reflection opportunities to continually adjust and be more intentional with your time and attention.

Talking to yourself

First, don’t just log tasks.

Vomit whatever’s on your mind onto the page, clear your mind fully of the last task to close any open loops. Then you’re more able to give the current task your full attention, and you’ll feel less distracted since you’ve got rid of those nagging thoughts.

Don’t be afraid to be verbose. Write as you think and talk to yourself. Don’t try to censor your thoughts. Don’t worry about spelling or grammar—you want the least amount of friction between what’s in your mind and getting it out onto the page in front of you. It’s just for you, so write naturally about whatever’s floating around your head. It could be how you’re feeling, your current emotions and random thoughts on any topic.

Thinking and Organising

Writing is thinking. The lightweight structure of IJ gives you a perfect place to think through the work you’re about to do. As a result,** you get a chance to evaluate your work more objectively rather than unthinkingly barrelling straight into the next task**.

Take a few extra minutes to potentially save hours of your time later. Then, when you think through what you’re about to do, you may realise that there’s a better approach, or it’s simply unnecessary.

Outliners, like Roam Research, make thinking and organising your thoughts easy. In Roam, by breaking your work down using the outlining features and keeping ideas related to it under appropriate pages or tags, you’ll also get an automatic work log for that project.

Keep a window open and ready to note what comes to mind during the task will help to keep you focused on the primary task at hand. Whether it’s how you feel as you progress, distractions that cropped up (and why), or just to quickly capture any other thoughts that spring up during your work.

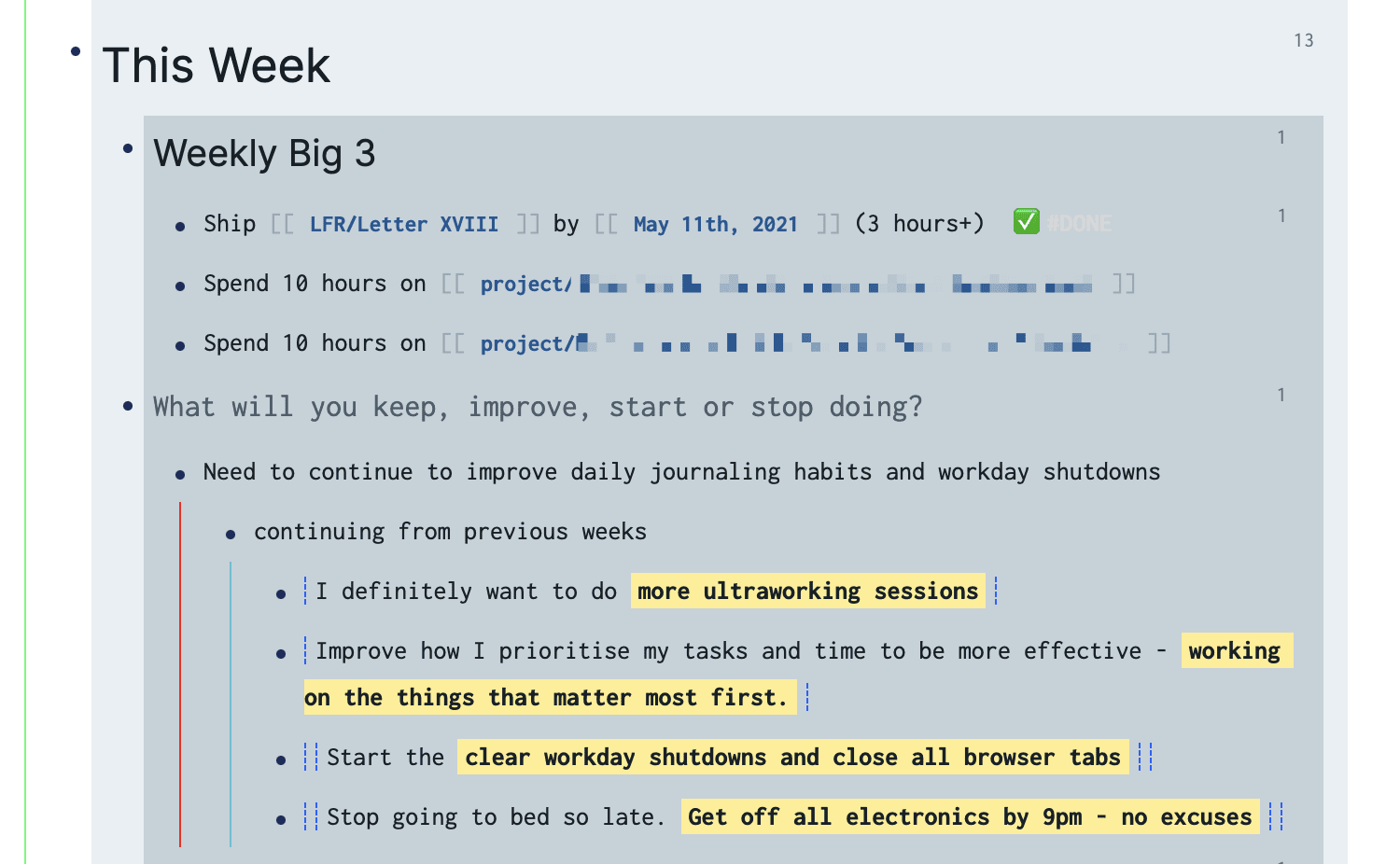

Extra focus for long work sessions

The act of Interstitial Journaling is often enough, but when you have longer, deeper sessions of work, it is easy to become too focused on what you’re doing and going with the flow, following your trails of thought and forget what your goal of the session was.

I’ll save the details for another article, but UltraWorking is a form of Interstitial Journaling on steroids. It breaks your long sessions into shorter work cycles, giving you periods of intense focus, followed by a short period to reflect and recharge before you go again. I think of them as HIIT workouts for knowledge work.

Semantic goldmines

Being verbose about what you’re doing and how you feel as you progress through your day will reveal patterns about your behaviour hidden in plain sight. If you’re writing naturally as you’d talk without censoring yourself, the language you use will shine a light on your hidden behaviours.

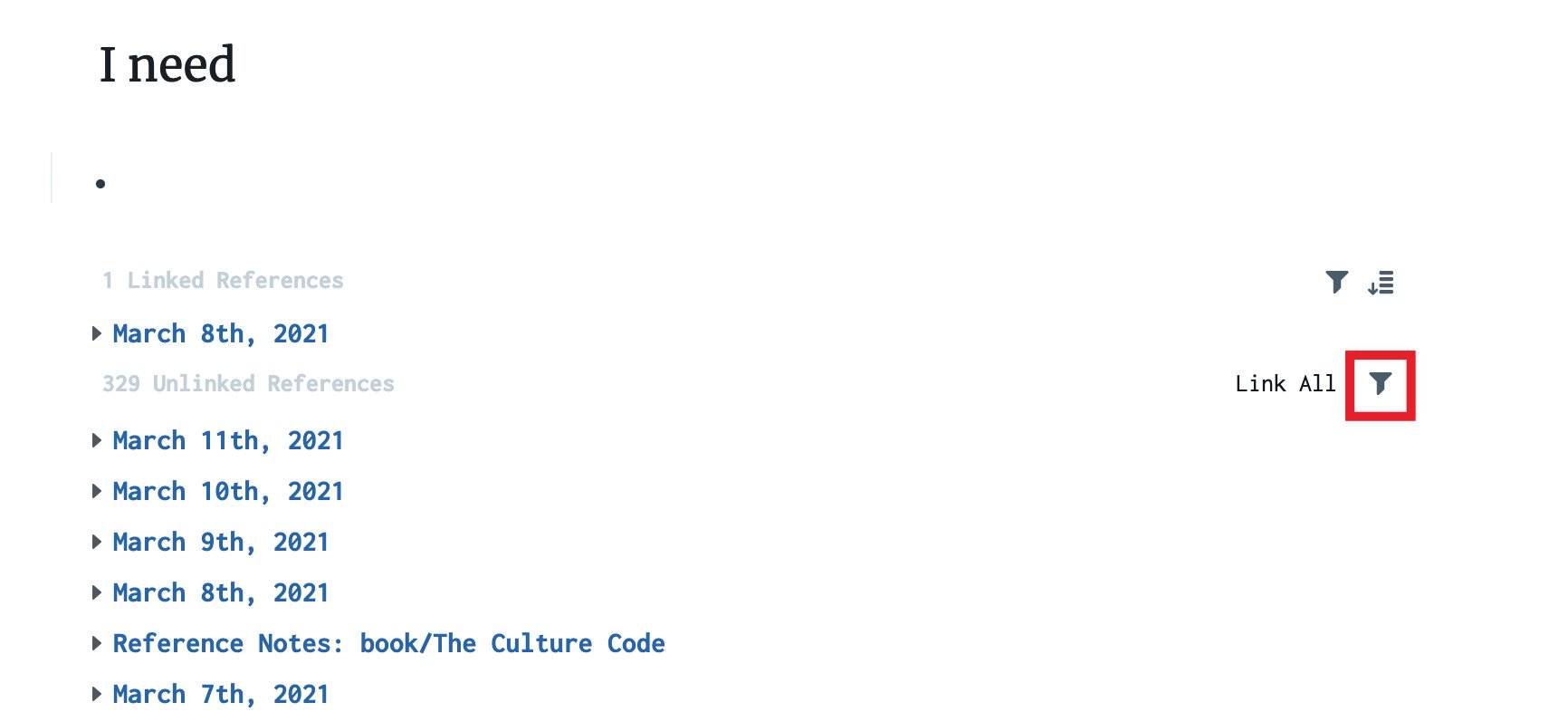

Again, Roam makes this effortless. Create pages for the common phrases you notice you use or patterns of speech you imbue with meaning and browse the unlinked references.

For example, a friend of mine realised he would use the phrase “Course Correct” whenever he noticed he needed to change direction. Matt Brockwell coined the term “Semantic Goldmines” to describe the gold hidden within your words.

I find that I write “I need” or “I want” a lot more than I imagined. Here are a few more phrases you could try:

- instead of

- could have

- might be

Look for your behaviour patterns. Twitter or Slack distracting you from the task at hand? When you notice this happening, jump back to your IJ. Spend a few moments to dig deep and question yourself. Ask yourself why.

Perhaps you discover how there’s often something prior that triggers a certain foible. Now you can put some steps in place to adjust and monitor your behaviour. When you have insight into your actions or learn a valuable lesson, add a tag to the note. If you do something daft, tag that too. I use “lessons learned” and “facepalm”.

Identify your mental and physical peaks and troughs. Note how you’re feeling, and use the Semantic Goldmine tagging technique to explore them over time to learn how and when to work best on what types of work. Then, use that information to manage and plan your days accordingly.

Review Cycles

As I mentioned earlier, IJ enables us to review our actions more frequently throughout the day. When you start doing this practice consistently, you may be surprised just how much happens in a single day. At the end of the day, it’s worth taking a few minutes to review your entries. Is there anything you learned you want to try to take into tomorrow? Write those down too.

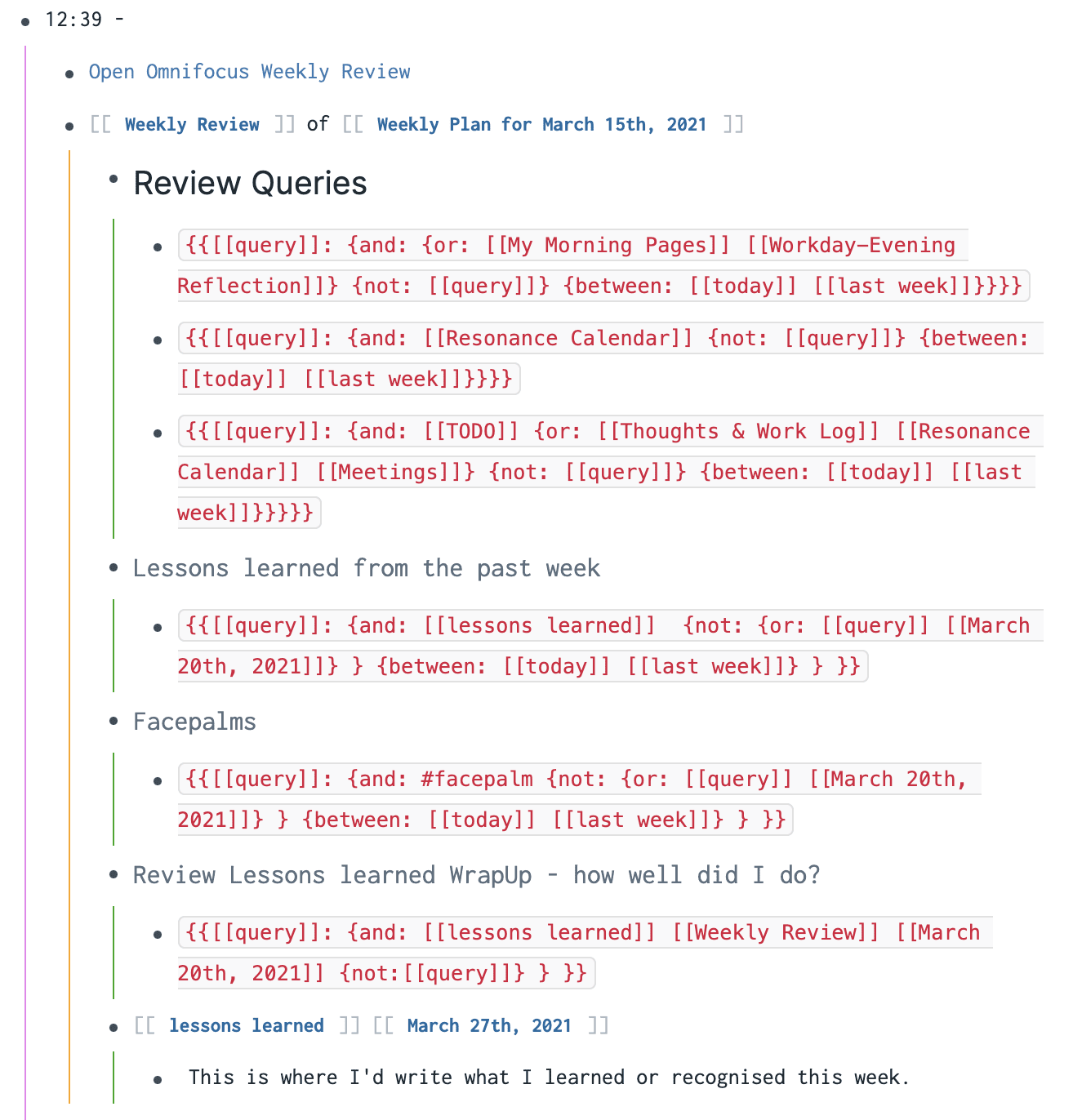

At the end of each week, I do a weekly review. I use the opportunity to resurface the lessons I learnt and to review my “facepalm” moments.

Roam makes this easy with queries.

I then distil the lessons I learned (or didn’t) as an overview of the past week. I repeat this pattern monthly and quarterly so that I have an ongoing log of my behaviour. I can see how far I’ve come, and it gives me a helpful frame of reference.

I like to embed what I learned in my Daily Notes template to keep them visible, otherwise out of sight, out of mind.

This is a form of Programmable Attention.

Learn. Commit. Do

Interstitial Journaling gives us a lightweight framework for being more intentional with our days. Or, to put it another way, Interstitial Journaling creates a gap between stimulus and response.

It is simply a way to shorten the feedback loop between experiencing and reflecting, and you learn best when that loop is shorter.

However, when you start out, you’ll almost certainly fail to do IJ consistently. Don’t beat yourself up, though. Instead, use those misses as a chance to learn from your failures. Aim to habitualise the practice through consistency and a standard, not perfection. For example, set yourself some increasing targets to hit 3 entries per day, then 5, then with no gaps and so on.

There is no one way of doing things. I have only laid out my experiences and practices here. Experiment and do what works for you. There are as many other ways of doing this as there are people. In this video, my friends RJ Nestor and Tracy Winchell discuss Interstitial Journaling and show their practices, and they are considerably different to mine; however, we all have the same goal:

Moving along the upward spiral requires us to learn, commit, and do on increasingly higher planes. We deceive ourselves if we think that any one of these is sufficient. To keep progressing, we must learn, commit, and do—learn, commit, and do—and learn, commit, and do again. — Stephen Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

I like to think of it as Intentional Journaling.

roam, note-taking, productivity, journaling, intention